Talk about A Singular Christmas at the Automatic Music Hackathon

I gave a talk about my A Singular Christmas at the Automatic Music Hackathon last week. Here’s what it looked like and what I said.

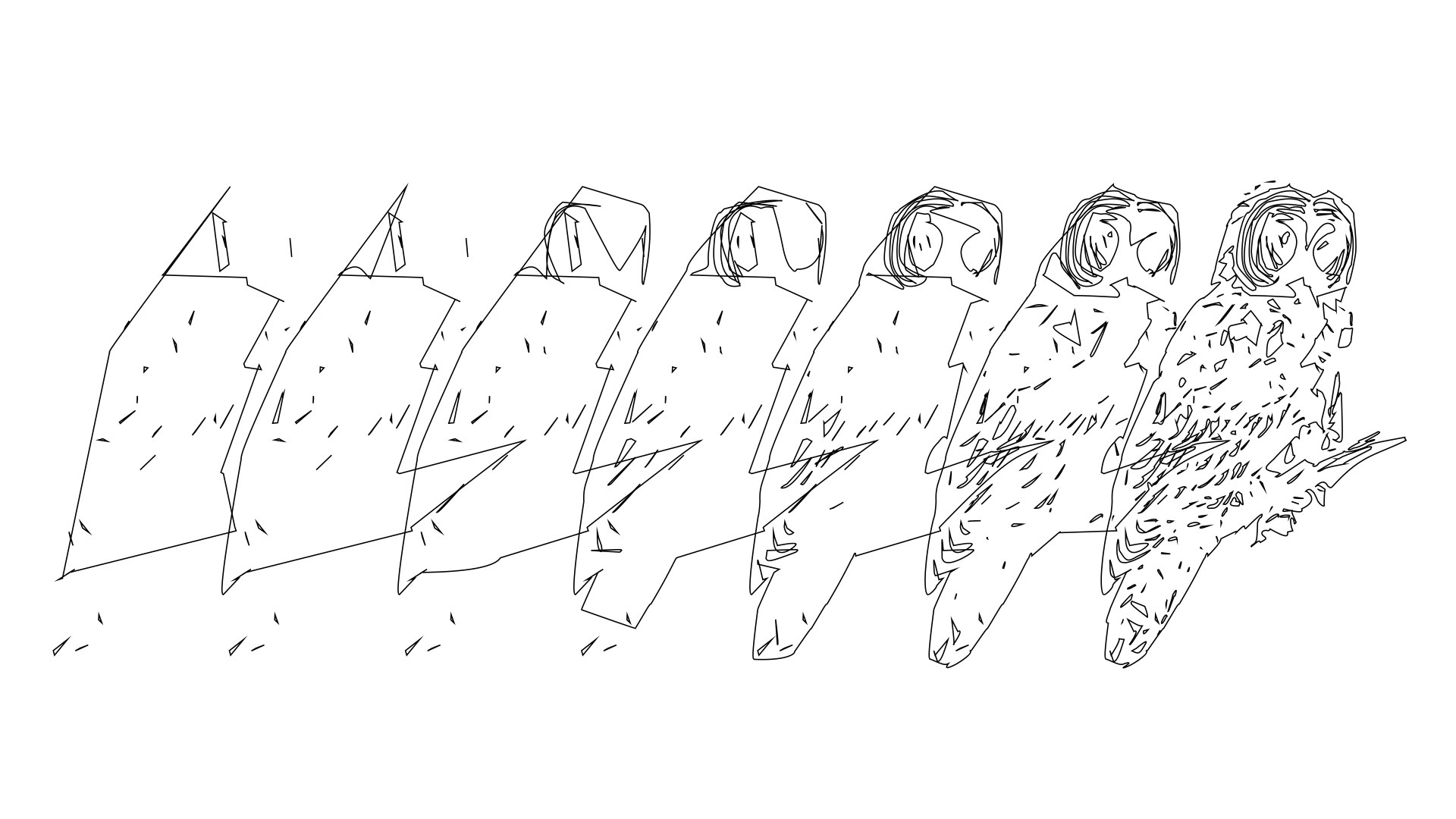

Pretend that you’re new here, and you want to know what a bird is. You’re lucky: lots of people know what a bird is. They can show you a bird. This is Hilary Putnam’s linguistic division of meaning, semantic externalism. If you see enough things labeled, Bird, you start to get a handle on what makes a bird a bird. They’ve got a beak or a certain color, they land on a branch, they spread their wings and fly.

[vimeo 81150169 w=500 h=281]

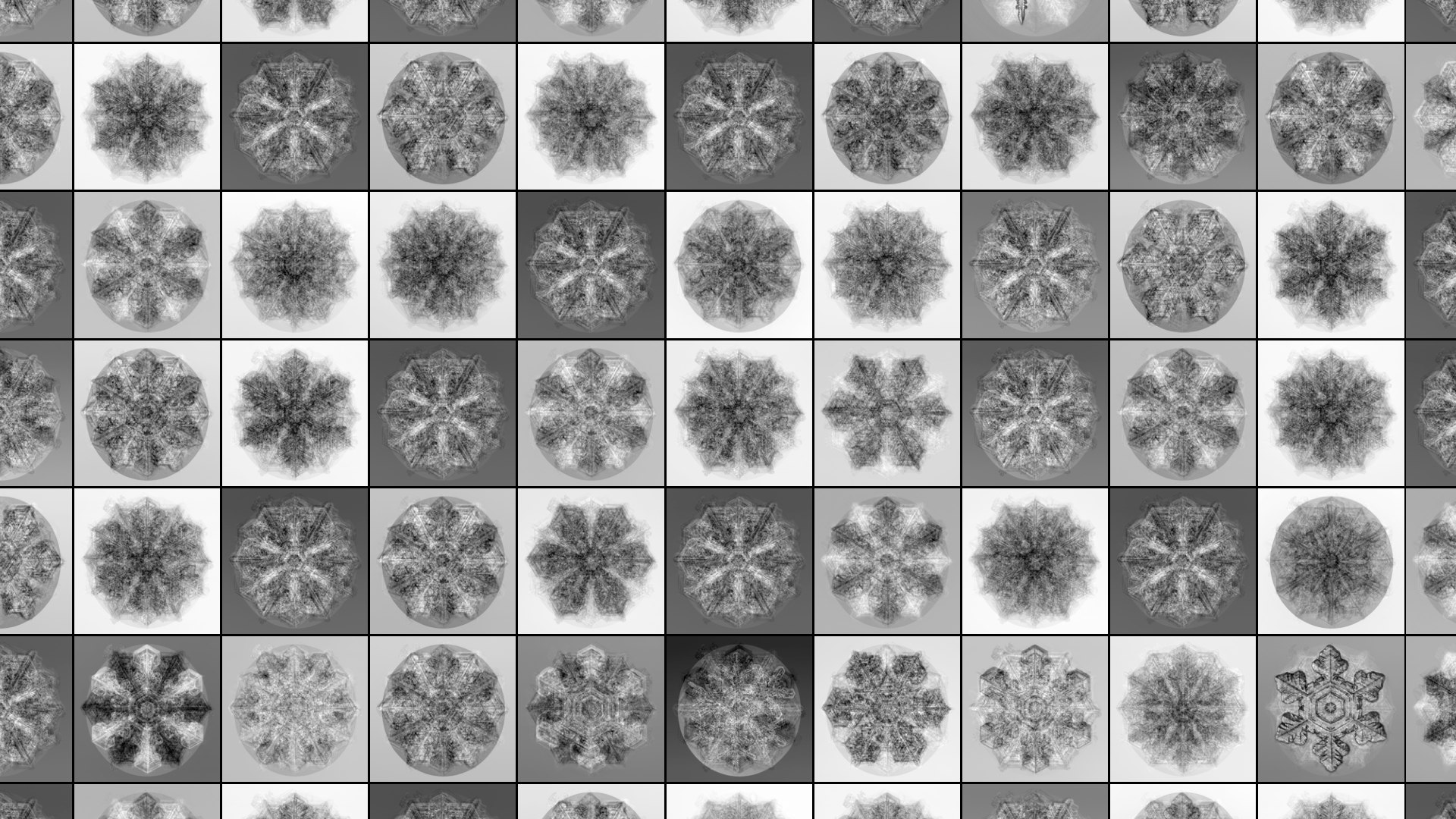

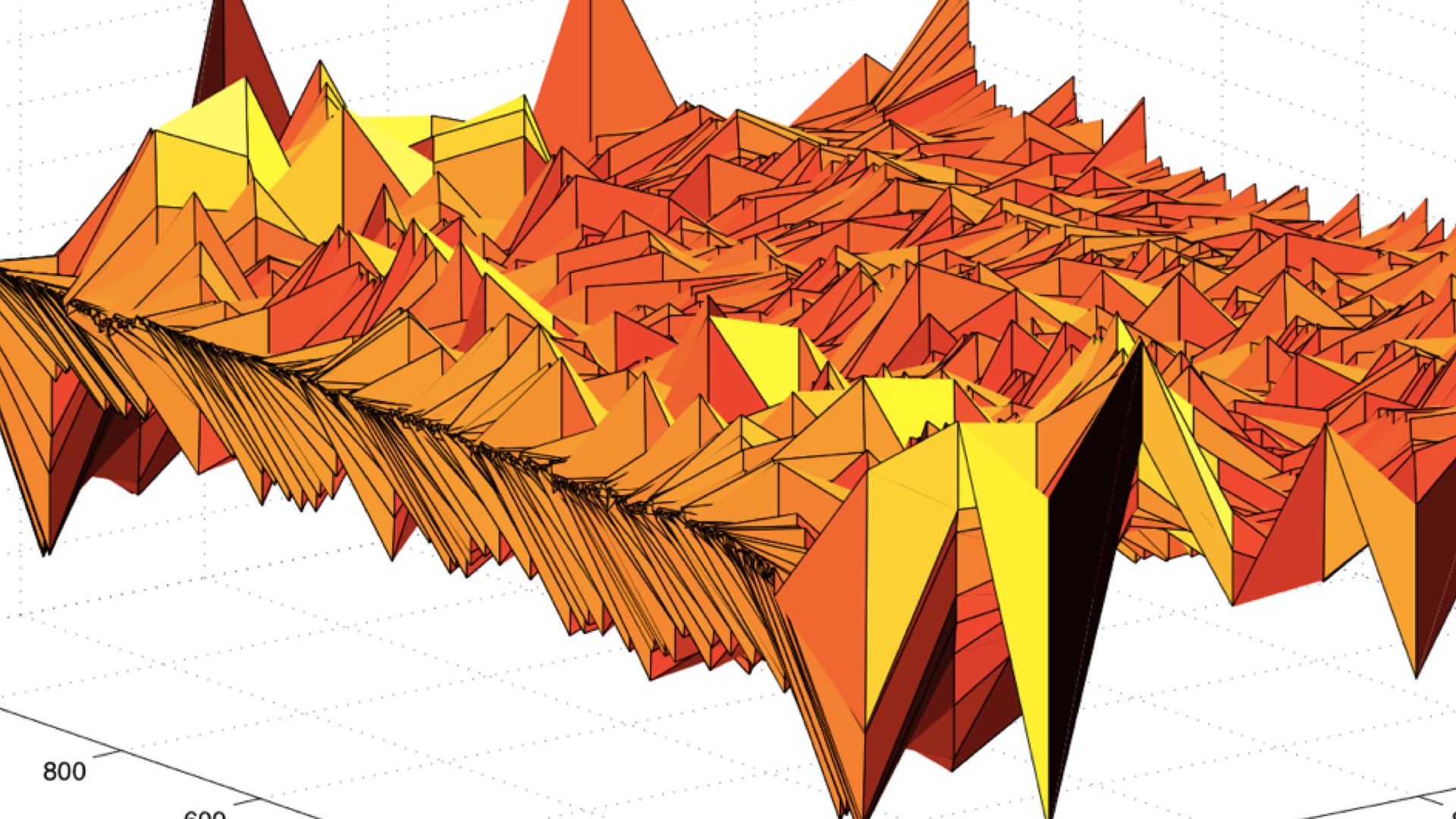

The way I’ve ever understood anything is by endlessly imagining all its forms and presentations. Watch what’s similar and what surprises you. See enough of the same thing, and you can make a little machine to describe it. Snowflakes maybe are circles, except when they’re not. Sometimes fractal edges, sometimes straight, sometimes a number describing the fractalness. Sparkles on the edges, a water droplet from the microscope? So any new snowflake is a set of machines you can add up. Circle plus fractal edge plus sparkles equals your own snowflake.

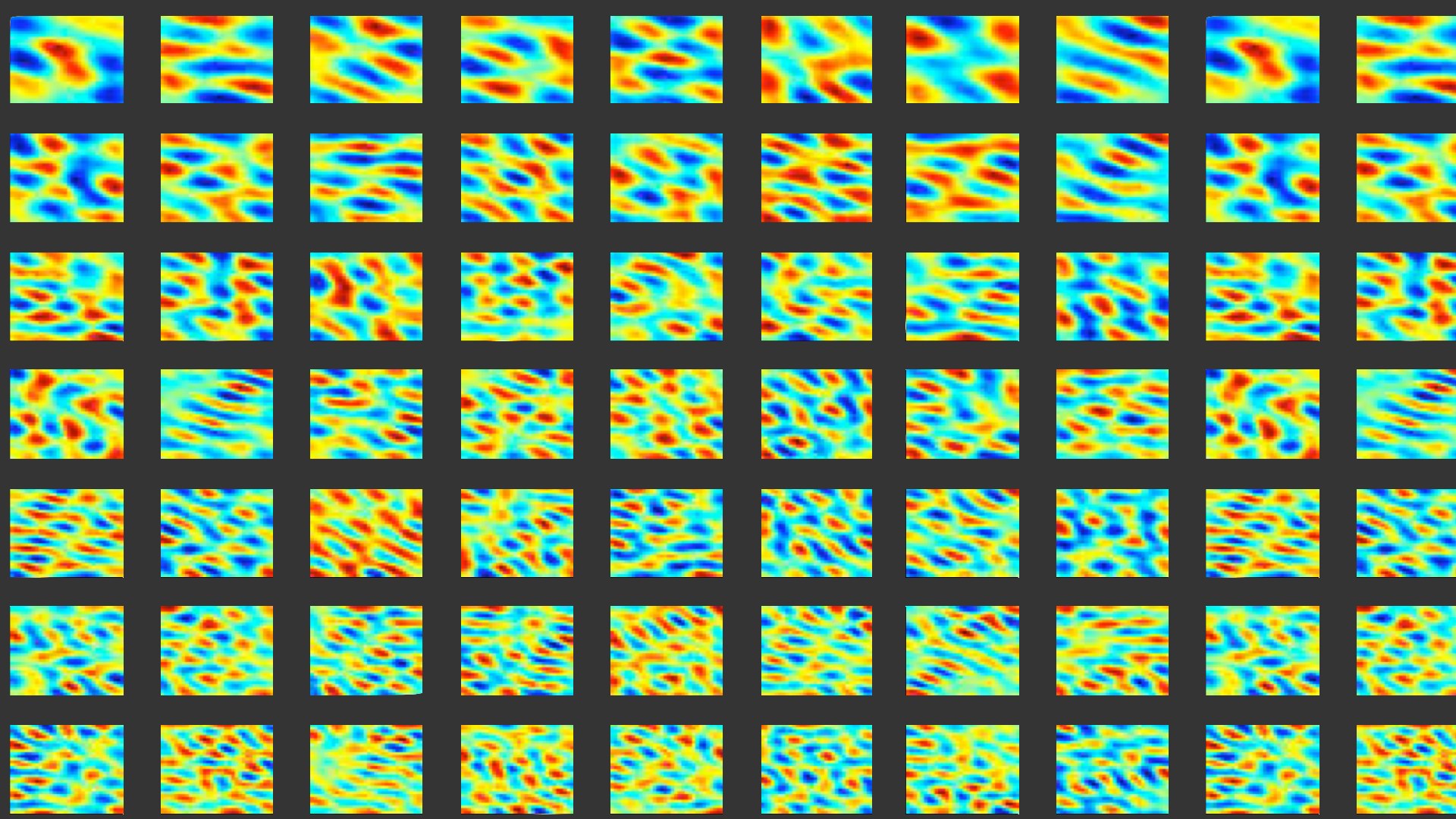

We’ve all done this. We treat pictures like this, movies, touch. And of course every sound you hear these days is a series of multipliers of a basis function, spit out a speaker so fast you can’t hear the buzz. Add a bunch of component bits together to get your creativity or expression. Rehydrate the vectors into a speaker or screen again, and you probably don’t even notice.

It’s in Pentland’s eigenfaces, so many years ago. You probably walked in the path of a dozen cameras trying this trick on your own face on the way over here tonight. Your phone has it built in, tries to tell if you’re smiling or maybe if you’re someone the government should know about.

But it fails more often than you can imagine. Vision guys call this registration. For a computer to get what something is, it’s got to line up. Keep the eyes in the same pixel. If someone is bigger than someone else. Or an outlier, like Facebook deciding your fishbowl is your grandmother. This is where we’re still better. We don’t normally confuse people with objects, and you only need to do that once. It turns out computers like skipping over repetitive things, and we appreciate those. It turns out computers get confused by loud noises.

I try to make this work better. I like when it fails, often, better than when it works really well. The algorithm annealing into a steady state has to be our culture’s greatest art. That we even had the hubris to encode our senses into a square floating point matrix of numbers. And that we even think that representation is good enough to understand the underlying thing.

I mostly do it with music. People know pretty much everything about every song ever, and there’s databases where you can get the pitch of the tenth guitar note, and what people said about it. Imagine the entire universe describing a song. And then you have the audio, too, and some computer-understandable description of all the events in the song.

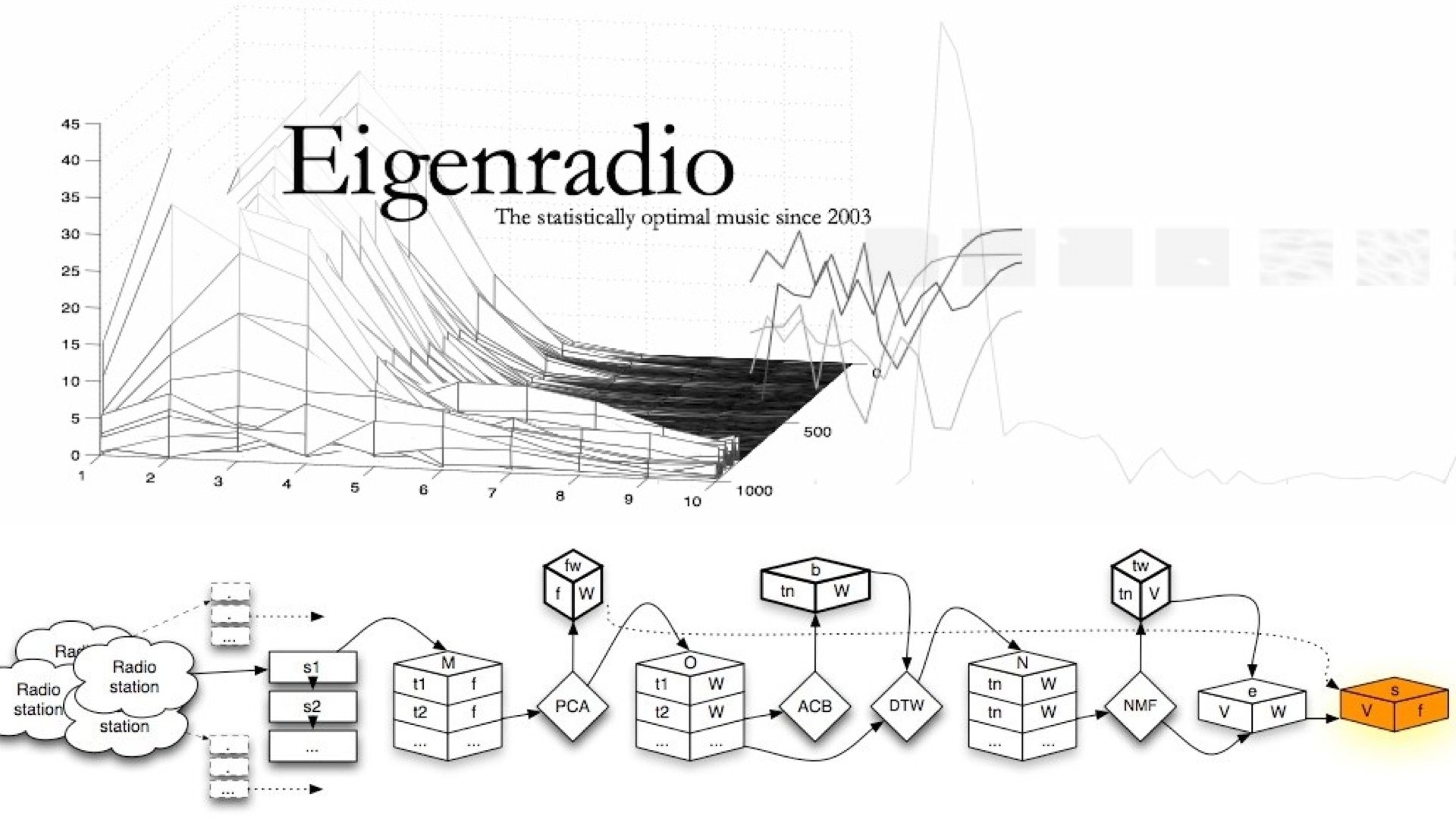

I’ve been doing it for a while, this was 2003, a thing called “Eigenradio.” it took every radio station I could get in a live stream at the time, at once, and figured out how to do basis computation and resynthesis in a sort of live stream back. The idea was to be “computer music.” Not music made on a computer, because everything is. But music for computers. What they think music actually is. It mostly sounded like this:

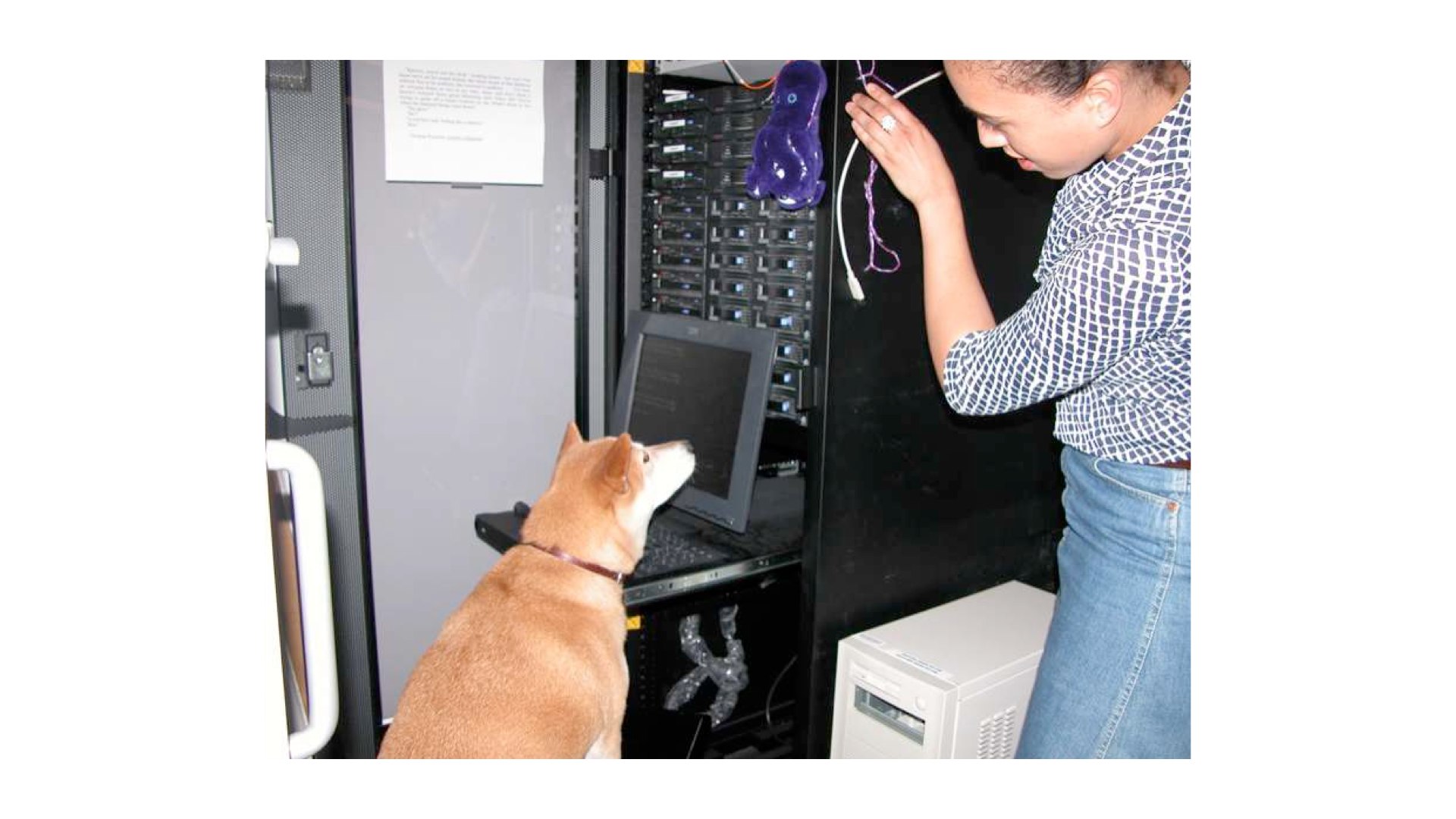

It took a lot of effort to do something like this. I taught myself how cluster computing worked, and scammed MIT into spending far too much money on something would be a free tier on a cloud provider these days. The power kept going out. But the project was my favorite kind of irony, the one where the joke is nowhere near as funny as the reality it pokes at.

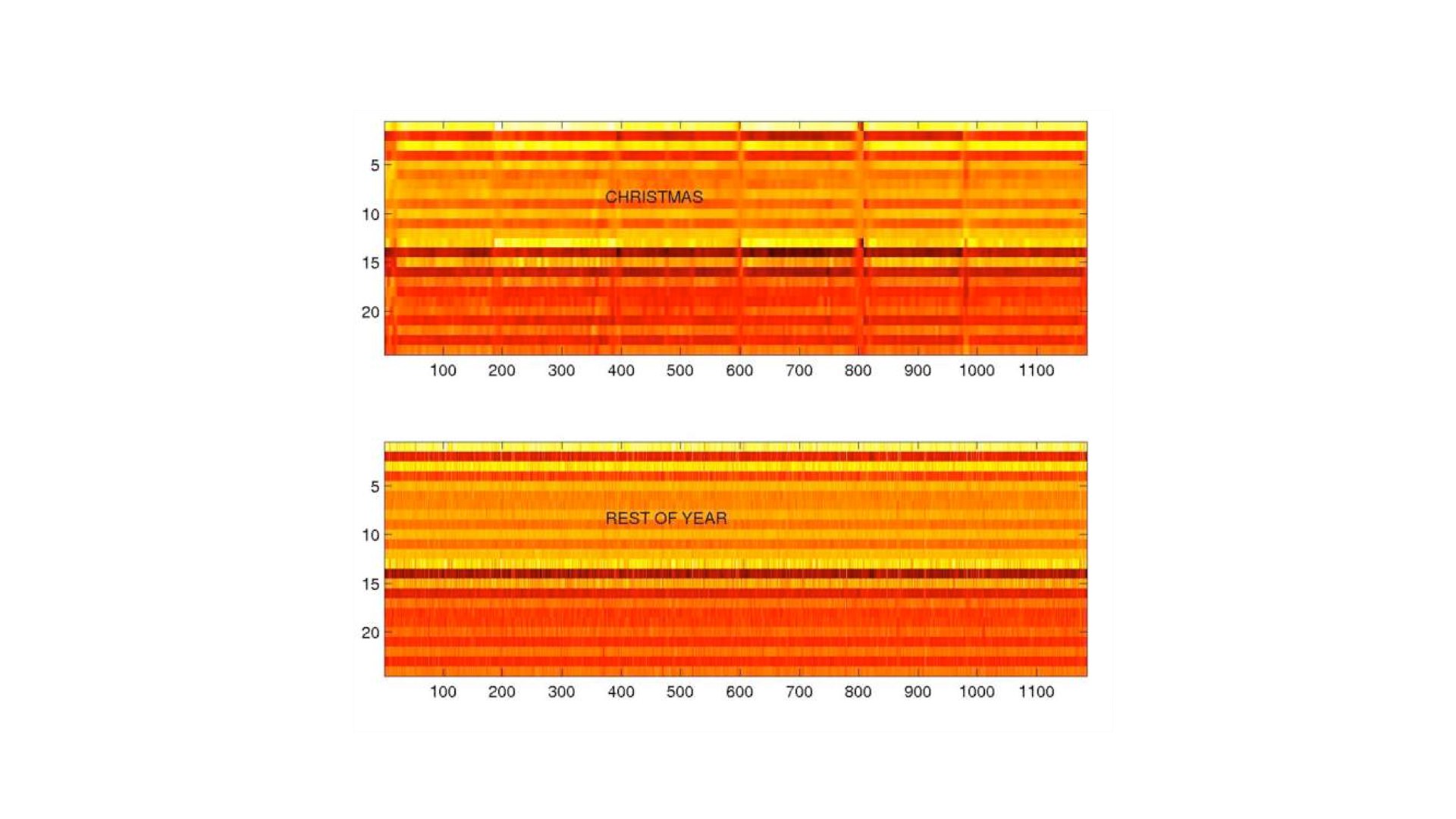

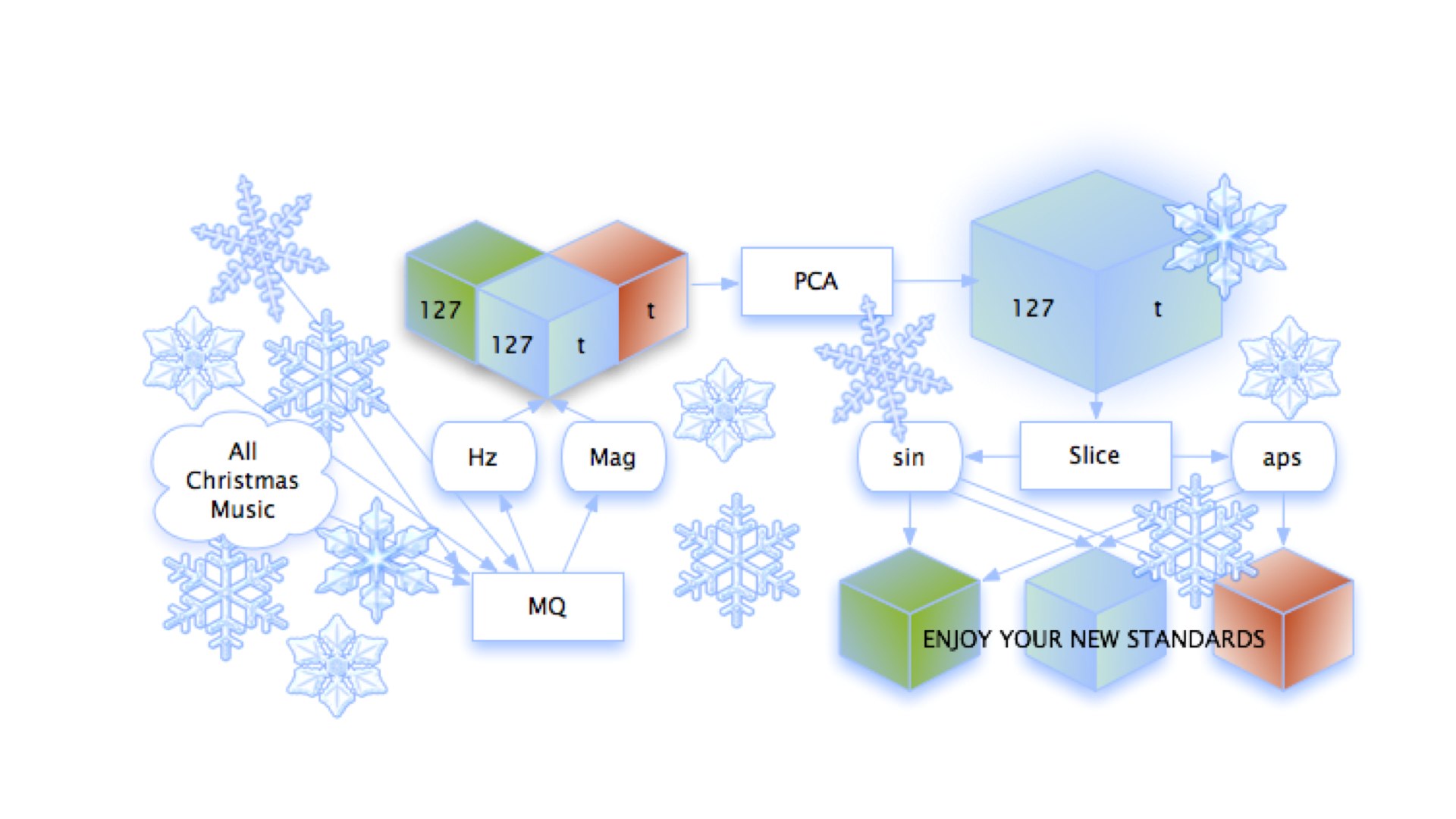

I have this whole other life that I’m not going to get into, but it involves knowing about music. Consider Christmas song detection. Thought experiment: imagine someone that doesn’t know Christmas, and you play them a bunch of Christmas songs, will they see a connection? Is there something innately Christmas about the music? Bells? Wide open melodies like a rabbit hopping on a piano? My theory was, if I could synthesize Christmas music from an analysis of all the Christmas music I could find, and people thought it sounded Christmas-y, we’ve cracked the code, we can have a Singular Christmas.

Do you want to know the magic trick? But doing this taught me one important lesson: synthesis is just fast composition. Computer people love to hate themselves because everything is so easy. But we all make things, often beautiful things, even if we didn’t mean to. Even if “the data did it” or you just threw a bunch of Matlab functions together or it only started sounding good when you started panning the sine waves into different channels. You’re composing.

This thing got everywhere. By far the most successful creative thing I’ve done. I was on the BBC on Christmas Eve, exasperatedly spelling out “eigenanalysis.” Pitchfork reviewed it, I got 4 stars. The MIT sysadmins and I had a big fight over its bandwidth. This excited Canadian man, on the radio.

My favorite things are the emails. Every December, right around now, they start slowly rolling in. How this album is the only thing they listen to during the holidays. How it means Christmas to them. I’m still working on this stuff, as a sort of hedge against my more mundane realities. I want to show the world there’s beauty in the act of understanding.